Many theoretical disagreements about measurement center around content validity. For example, if one’s theory of intelligence includes creativity as a component (creativity is part of the ‘content’ of intelligence) a test cannot be valid if it does not measure creativity. But given how much flat-Earth beliefs contradict basic science and information from official channels like NASA, we might also include questions that measure trust in science (e.g., The scientific method usually leads to accurate conclusions) and government institutions (e.g., Most of what NASA says about the shape of the Earth is false).Ĭontent validity is one of the most important aspects of validity, and it largely depends on one’s theory about the construct. Obviously, the scale would need to include items measuring people’s beliefs about the shape of the Earth (e.g., do you believe the Earth is flat?). An assessment of content validity would judge how well these questions cover different conceptual components of the flat-Earth conspiracy.

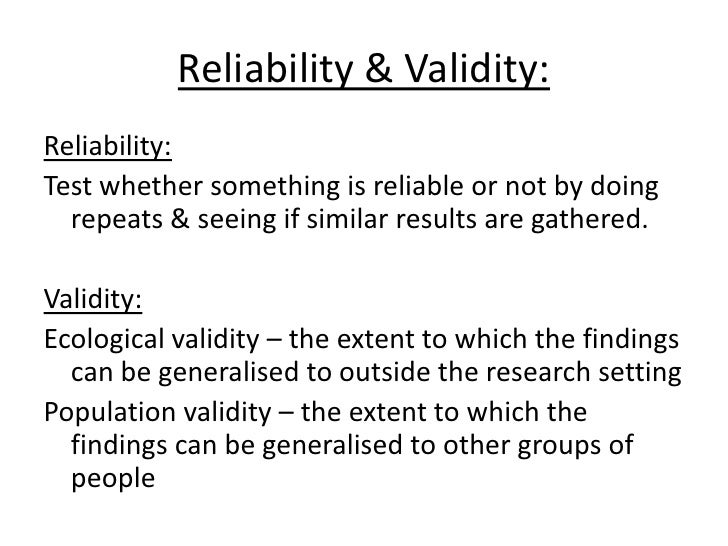

Within the context of survey research, validity is the answer to the question: does this research show what it claims to show? There are four types of validity within survey research. Validity refers to how reasonable, accurate, and justifiable a claim, conclusion, or decision is. Thus, we lay out the details of both constructs in this blog.

However, understanding validity and reliability is important for both the people who conduct and consume research. Digging into these concepts can get a bit wonky. Nevertheless, behavioral scientists persist, using surveys, experiments, and observations to learn why people do what they do.Īt the heart of good research methods are two concepts known as survey validity and reliability. They may not always want to divulge what they really think or they may not be able to accurately report what they think. Let’s start by agreeing that it isn’t always easy to measure people’s attitudes, thoughts, and feelings.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)